In March, Dr. Regis Kopper helped organize the first large-scale conference to take place entirely within virtual reality.

Now, the UNC Greensboro computer science professor is applying virtual reality to remote telehealth visits, meaning we may soon experience our doctor as being in the room with us, even if that room is our own living room, and our doctor is actually miles away.

With COVID-19 forcing people to remain physically distant, could virtual reality enter the mainstream sooner than expected? Kopper, who specializes in the immersive technology, believes so. Here he talks about what COVID-19 could mean for the future of virtual reality—and its impact on our lives.

COVID-19 as a catalyst

Technology has already rapidly transformed during the pandemic. The video teleconferencing software Zoom, for instance, saw a 30-fold increase in users in April 2020. More and more people are also visiting their doctors virtually, with telehealth usage increasing 4,347 percent in the U.S. over last year.

“I see COVID-19 as a disruptive event, like a war,” said Kopper. “During WWII there were decades worth of development within seven years—weapons, communication systems, transportation, medicine. With COVID-19, we have a little bit of the same opportunities for developing technologies to support physical distancing.”

He expects funding for VR research to increase dramatically as the pandemic creates a renewed interest in and market for virtual reality technology.

So far, VR has primarily made its way from the lab to the consumer market through the entertainment and gaming industries; however, the use of VR has been steadily growing in health care, the military, education, and other industries. Kopper recently developed a project using VR to enhance public safety technology; funded by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the project prototyped an augmented-reality armband for police to use during traffic stops, giving them an increased awareness of their environment. Watch the demonstration.

Virtual reality in health visits

Now Kopper is shifting gears by applying virtual reality to health care. He recently received funding from UNCG’s Faculty First program for a project that would make telemedicine visits much more … realistic. While telehealth has grown in popularity, the technology has its limitations.

“A lot of times, the doctor needs to see your whole body to see how you’re walking, your posture, or follow large body movements,” said Kopper. “For that, video alone is probably not sufficient.”

That’s where VR comes in. Kopper’s new project would design a prototype in which the doctor wears an immersive virtual reality headset, and the patient—in an entirely separate location—is set up with a 360-degree, spherical camera with a live feed. The combination of the VR headset and 360-degree video would allow the doctor to feel fully present in the patient’s room; the doctor could turn around in the patient’s setting, observe the remote location from all perspectives, and most importantly, get a full-body view of the patient.

Ultimately, Kopper hopes to “close the loop” by enabling the patient to experience the doctor as being in their room as well.

“The patient would have an augmented reality device that will render a representation of the doctor in their location,” he explained.

While such technology may seem expensive, the cost to supply a patient with a 360-degree camera is less than the cost of a consultation, so it could easily be covered by health insurance.

It is clear to see how such immersive remote health visits would be helpful during a pandemic, allowing at-risk populations and those living in rural areas safer and easier access to health care specialists. Yet this research also has important implications for global health. By combining 360-degree video on one end, with a VR headset on the other, we could bring health specialists to remote corners of the world without expensive air travel.

“Countries like Uganda, for example, have very few neurosurgeons—like four or five in the whole country,” said Kopper. “Add to that, the likelihood of head traumas in developing countries is much higher than in the U.S. So the idea here is to leverage virtual reality by bringing a remote surgeon into another country’s surgery room. Of course, they can’t perform the surgery, but they can give guidance on what should be done.”

The future of VR

While virtual reality may seem like something out of a science fiction movie, Kopper and many others believe we are not far away from seeing VR (and its cousins: augmented reality, mixed reality, and extended reality) popping up in our everyday lives—from health care to policing to maintenance. COVID-19 has likely accelerated VR’s timeline as the demand for remote connectivity grows.

So what does the future of VR realistically look like?

“For a true, ‘Star-Trek’-style remote Holodeck type system, we can be centuries away if we think of actually simulating matter,” said Kopper. “But for something like where you’re seeing another person as being in the room with you, and that person is seeing you as being in the room with them through augmented reality, I’d say 5-10 years we’re going to start seeing that more and more.”

Virtual reality, it seems, may be an important way of staying connected in a more physically distant world.

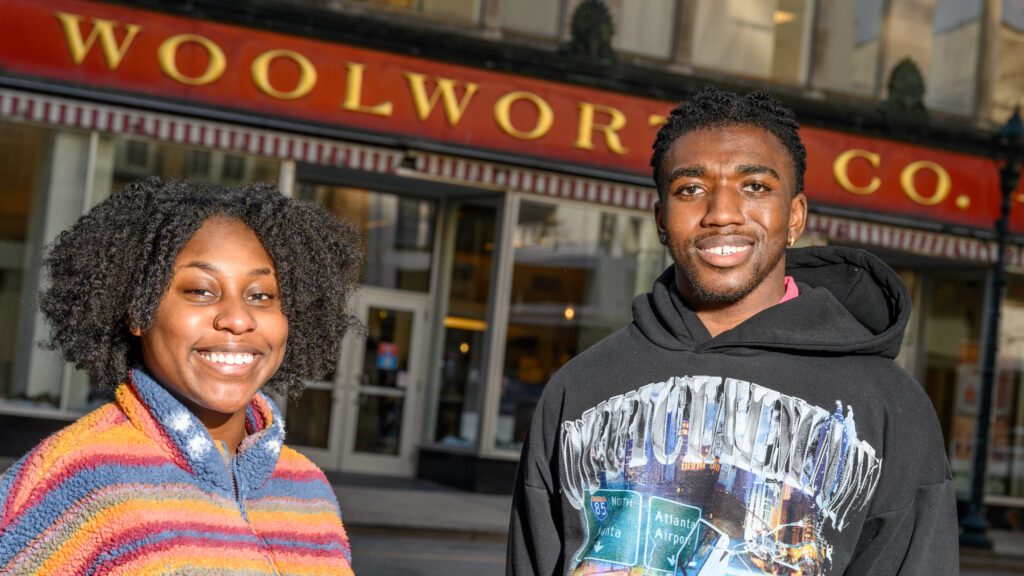

Story and photography by Elizabeth Keri, College of Arts & Sciences